The Single Visionary Fairytale

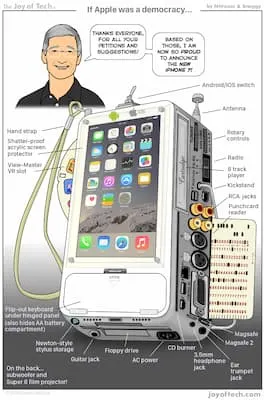

There’s a single panel comic, made in 2016, that tends to resurface every once in a while. The comic shows an iPhone that is overloaded with ridiculous features: a flip-out keyboard, extendable radio antenna, handstrap, AA battery compartment, kickstand and more. The title of the strip is simply “If Apple was a democracy…”.

I saw it again the other day as someone shared it, with a cautionary reminder that decisions about technological products cannot be a democracy. The image is comical, and I think all of us can think of products that have gone a little too far in this direction.

But the thing that bothers me each time I see the comic is that it pushes the problematic “single visionary” narrative.

At best, it’s a dangerous and risky mindset. At worst, it can be quite toxic.

The genius myth

We have a tendency to want to look for the single genius—the one individual who is a visionary, who knows what users need better than they do themselves, who knows what a product should or shouldn’t do. They don’t need to talk to users, they don’t need to confer with others. They have a powerful vision in their mind of what needs to be done, and they have their team make it so.

It’s a damaging fairytale that results in a bunch of people who think they’re that person. They think they know best. They don’t need to talk to users. They don’t need to look at the data. They don’t need the people around them to come up with the ideas. They just need people to listen to what they have to say and execute on the decision they already know to be correct.

99% of the time, those people are just flat-out wrong.

Maybe they have a small series of successful decisions that encourages them for a bit, but inevitably things fall off the rails. In their wake, they leave a trail of destruction. The people around them are discouraged and demoralized because they’ve never been empowered to make decisions themselves. There’s no established culture of exploration and learning. So when things start to go amiss, the framework isn’t there to recover.

The idea that product decisions can or should be made by a single visionary mind is the root of so many failed attempts to create the next great thing.

Doing better

So if the visionary is a rarity, how do you make product decisions that will end up with a product that is useful and valuable and not overrun with every random idea?

You do, in fact, start with a vision, but not about execution—it has to start with something more open than that. You start by figuring out what it is that you’re setting out to build, and for whom. What are the principles you want your product to reflect.

These principles not only help you figure out what you want to build, but they help you figure out what not to build as well.

Principles like this are important because it means you don’t have to sit there and put your fingers in your ears to avoid the “overly complex iPhone” scenario. Instead, you actively listen and explore so that you can discover new ways of aligning with them.

With these principles in mind, the next step is to have a mindset of humility and curiosity. In my opinion, these may be the two single most important characteristics for success in developing products.

Never assume you know the situation, do the work to learn.

Talk to your users, regularly. The more regularly the better. I try to have at least one call with a user a week, more if there’s a specific question I’m trying to answer. However frequently you do it, the point is to not wait until you have a question you need answered, but to make it continuous. These calls are for listening. Find out the problems folks are trying to solve, the way they’re using your product, the gaps they still have.

Look at the data. Measure what you can about how your product gets used. When you come up with a new feature, think about what you’re trying to accomplish with it, and how you might measure its effectiveness. Spend time exploring the data to see what you can learn about how people use the things you build.

Always make a point to challenge your assumptions. If you’ve got a hypothesis in mind, that’s great. But then go look for the evidence to either support it, or to prove it wrong.

It can be tempting to only look at data that will build your case, but that’s really just the same problem as the “visionary” narrative. One thing I like to do before diving into the data is to make a list of questions that I want to answer. I think about the questions that would support my hypothesis. But then I also think about the questions that someone might explore that could disprove my hypothesis. My goal is to have an even number of both.

Most importantly, and in sharp contrast of “don’t make decisions like a democracy”, involve those around you. Presumably, you’ve got smart people in your organization that care in some way about what they’re working on. Giving them marching orders and expecting them to just follow is such a waste of that talent.

Instead, arm them with the vision and guiding principles, and then solicit their feedback constantly. The idea is not to push a solution on them, but to instead give them the problem and see what sort of solutions they come up with. Make sure you’re giving them ample time to take a step back and think big picture.

If you can, involve them in the user conversations and data analysis. If you can’t, at least share those with them on a regular cadence. They’ll feel more involved and in no time, you’ll have a robust set of great ideas flowing.

The ultimate goal is to create an environment where everyone feels like they can provide input and ideas on the future direction of what you’re all building. Simply giving people the space and respect to contribute will do wonders for your product.

As Jeena James—one of my favorite people I’ve ever worked with (and a great example of humility and curiousity in leadership)—likes to say “It’s incredible what can be accomplished when no one cares who gets the credit.”

That’s what you’re after. That’s how products and companies succeed. Not by a single, all-knowing visionary, but by the collective input of a group of people working on the product, informed by data and continuous user conversations, and framed by a series of principles that you want your product to reflect.

We should be much more afraid of the “single visionary” narrative than we should of making our product decisions more democratic.