Performance Budget Metrics

Yesterday, Chris Coyier pondered aloud the best metric to use for a performance budget:

Re: performance budgets. I wonder if measuring times is smart or not. So many variables, seems like requests/sizes/blockers easier to track.

It’s an interesting question, and one that I touched on at the beginning of the year. I think it’s worth elaborating on a little.

The purpose of a performance budget is to make sure you focus on performance throughout a project. The reason you go through the trouble in the first place though is because you want to build a site that feels fast for your visitors.

One of these goals (prioritizing performance) is an internal one impacting the people who are creating the site. The other goal (building a site that feels fast) is an external one impacting people who visit your site. It’s not surprising that I’ve found the most effective metrics to differ for each.

For the purposes of this post, I’m breaking those metrics down into four categories:

Milestone timings

Examples: Load time; domContentLoaded; Time to renderMost time-based metrics are “milestone timings” (totally stealing that term from the super smart Pat Meenan). Some (like visually complete or time to interact) are closer than others to telling you something about the experience of loading a given page, but they all suffer from the same limitation: they measure performance based on a single point in time.

Web performance isn’t defined by a single moment. Like a book, it’s what happens in-between that matters.

Page A may load for 3 seconds, but not display anything to visitors until the 2.5 second mark. Page B may load in 5 seconds, but display the majority of the content after a mere second. Despite taking 2 seconds longer in total, Page B may be the better experience.

A single milestone timing won’t help you identify that. To get a semi-accurate representation of how it feels to load a page, you have to pair several milestone timings together. You can do that, but there’s a better way (hey there, SpeedIndex).

Still, milestone timings as budget metrics do have advantages. They’re easy to describe. Visually complete is a pretty easy to understand even without a working knowledge of performance.

They’re also easy to track. You would be hard pressed to find any sort of performance monitoring solution that doesn’t allow give you these sort of metrics.

It’s worth singling out User Timing marks as a better option than the default milestone metrics reported by the browser. They do require a bit more planning and setup, but because they are custom to your site they can also give a much more accurate depiction of how your page is actually rendering.

SpeedIndex

I’m giving SpeedIndex its own little category because it deserves it. Whereas traditional metrics focused on a single moment, SpeedIndex attempts to measure the full experience. It focuses not just on how long it took for everything to display on a page, but how the page progressed from start to finish. SpeedIndex scores are like golf scores: the lower the better.In our example from above, Page B would likely have a lower SpeedIndex score. It got most of the content onto the page early, so the page appears faster to load.

SpeedIndex gets a lot of love, and for good reason. It’s the closest we can get to putting a number to how it feels to load a page. But it’s not without its faults.

SpeedIndex is not the easiest of metrics to explain to someone without a certain level of technical know-how. Heck, it can be hard to explain to people with a relatively high level of technical know-how. It didn’t really click for me until I re-read Pat’s original announcement a few times and played around with it in WebPageTest.

The other downside is that at the moment it’s not a metric that gets measured by anyone outside of WebPageTest. While I would be happy if everyone would track performance using a private instance of WebPageTest, I understand that’s not likely. Hopefully Pat’s work on RUM-SpeedIndex will result in better adoption of the metric in other monitoring tools.

Quantity based metrics

Examples: Total number of requests; Overall page weight; Total image weightI’m going to lump request count, page weight and the like under this third category that I just made up for the sake of having something to call them.

Weight and request count tell you virtually nothing about the resulting user experience. Two pages with the same number of requests or identical weight will render differently depending on how those resources get requested.

Yet even they can play a useful role in performance budgets. Their main advantage is that they are much easier to conceptualize during design and development. It’s a lot easier to understand the impact of one more script or another heavy image on a budget of 300kb than it is for a SpeedIndex based budget.

Rule based metrics

Examples: PageSpeed score; YSlow scoreI’ve seen some people use PageSpeed or YSlow scores as budgets. For anyone unfamilar, these are awesome tools that give your site a grade based on a list of performance rules it tests against.

It’s really valuable as a checklist of optimizations you should probably be doing, but I think it’s less effective as a budget. While there’s a slightly stronger relation between these grades and the overall experience of loading a page than there is for quantity based metrics, it’s still a loose connection. A page with a higher PageSpeed or YSlow score doesn’t always mean the experience is better than a page with a slightly lower one.

Monitoring your PageSpeed or YSlow score is a good idea, but not necessarily for your performance budget. Use these tools as a safety net for making sure you haven’t overlooked any simple optimizations.

How I roll

My initial budget is always based on either SpeedIndex or some combination of milestone metrics. Which I use depends on the organization, what they will be using for monitoring, and how they will use the budget.

Regardless of the specific metric I choose, I always start here because these metrics relate in some way back to the user experience. They help keep tabs on the external goal: creating a site that feels fast for visitors. That’s what I’m most concerned with.

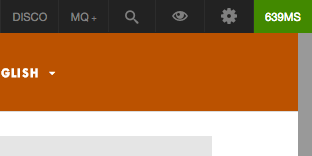

These metrics get incorporated into the build process (using something like grunt-perfbudget as explained by Catherine Farman) and in the development environment (like Figure 1) to make sure they’re monitored.

Figure 1: Enforcing a performance budget within Pattern Lab using some custom JavaScript.

After a few experiments to determine a rough equivalent, I pair those metrics with a quantity metric. Quantity metrics are helpful in achieving the internal goal: ensuring priority is given to performance throughout a project. They help guide design decisions. This is something Katie Kolvacin and Yesenia Perez-Cruz have each done an awesome job of discussing.

Each of these types of metrics play different roles in guiding the creation of a site, and each is important. It doesn’t have to be an either/or proposition.

Use rule based metrics to make sure you haven’t overlooked simple optimizations.

Use quantity based metrics as guides to help designers and developers make better decisions about what goes onto a page.

But always back those up with a strictly enforced budget using a metric (like SpeedIndex) that is more directly related to the overall experience to ensure that the result feels fast. After all, that’s why you’ve decided to use a performance budget in the first place.